Notable Properties of Specific Numbers

First page . . . Back to page 11 . . . Forward to page 13 . . . Last page (page 25)

(Meller's "370 property")

370 = (037 + 073 + 307 + 370 + 703 + 730)/6, which is the average of all possible permutations of its digits. It and several other multiples of 37 have this property for reasons that are discussed under that number. A larger example with a cool digit pattern is 456790123. Numbers with this property were first pointed out to me by Claudio Meller. Many larger examples are discussed here.

371 = 7×53 = 7 + 11 + ... + 53. Like 39, it is the product of two primes p1 and p2 and the sum of all primes from p1 to p2 inclusive. The next such number is 454539357304421 (see that entry for more).

371 is also the sum of the cubes of its own digits: 33+73+13 = 371; see 153 for more like this.

This number is called "automorphic", because it has three digits, and the last three digits of its square are the same: 3762=141376. I refer to this as "square automorphic" to distinguish from the "centered hexagonal" version, and other similar sequences like the triangular automorphics. Stated more precisely, n is (square) automorphic if n2=n modulo 10d, where d=floor(log10(n)+1). The automorphic numbers are: 0, 1, 5, 6, 25, 76, 376, 625, 9376, 90625, 109376, 890625, 2890625, 7109376, 12890625, 87109376, ... (Sloane's sequence A3226). See also 9103890995893380022607743740081787109376.

This is a palindromic prime, the sum of the first three 3-digit palindromic primes, and a Woodall number. The good folks at Numberphile made a video, "383 is cool",

This is π4 + π5, notable for being very close to e6 (which is 403.428793...). This was first reported to sci.math by Doug Ingram, who in July 1989 found it "[in someone's] .sig file", most probably Soren G. Frederiksen of Ohio State University:

4 5 6 PI + PI = e ????? Strange enough to be true.From the sci.math discussion thread it later entered the consciousness of David Wilson, who (around 1997) reported it to Eric Weisstein [171], from whom it made its way into MathWorld119, which describes the relation as

e6 - π4 - π5 = 0.000017673...

crediting Wilson. Another early reference is 52.

This near-equality can be easily discovered with my RIES "equation finder" program, using the command:

ries 3.141592653589 --min-match-distance 1e-8 -NSCT

which tells it to find near (but not exact) equations for π without using the trig functions. Among its output are the equations:

x√π+1 = e3/π

and

x2/e3 = 1/√1+pi,

Since we're trying to approximate π, we can change each x to π (and change the equal sign to a near-equality); then these equations are both equivalent to π4+π5 ≈ e6. Another equation output by the same RIES command is ex-π = 4×5, which yields another curious near-integer.

See also 23.140692632779269005... and the Ramanujan constant.

This is close to π4 + π5; see 403.428775....

A recurring "random number" in the webcomic Homestuck (the longest series in the MS Paint Adventures by Andrew Hussie). This page on the Homestuck wiki summarises appearances of the number.

For a while this number had a popular culture association with marijuana. Some anecdotes are at Urban Dictionary. See also 187.

This is a Catalan number, and shares with 27 the property that it is formed from the digits "4, 29" and is also the sum of the numbers from 4 through 29: 4+5+6+...+28+29 = (29-4+1)×(4+29)/2 = 26×33/2.

As reader Matt Goers points out, there aren't many such numbers: 15, 27, 429, 1353, 1863, 3388, ... (A186074 in Sloane's database) with about an average of three for each number of digits. 15 and 1353 fit a pattern which extends indefinitely: 133533 = 133+134+135+...+532+533 = (533-133+1)×(533+133)/2 = 401×666/2, and similarly for larger numbers like 13335333. If the first and last numbers are put together the other way (for example, 204 = 4+5+6+...+19+20 = (20-4+1)×(20+4)/2 = 204) we get another sequence of numbers (Sloane's A186076).

The smallest number that requires more than three terms to express as a sum of 3-smooth numbers, as in X = 2a3b + 2c3d + 2e3f + ... (the next record-setters are 18431, 3448733, and 1441896119). This type of representation of a number is referred to as a "double-base number system" (DBNS); see here.

432 = 24 33 which makes it 3-smooth. Like its factors 108 and 216, it occurs occasionally in religious and spiritual contexts, most often multiplied by some power of 10 (see 43200, 432000, 4320000, and 4320000000). 108 doubles to 216 and then to 432; if you keep doubling further, you get 864, 1728, and 3456.

(an order-4 Kaprekar number)

An example of an order-4 Kaprekar number: take an n-digit number, raise it to the 4th power, divide the result into 4 groups of n digits each, add together and get the original number. In the specific case of 433, the 4th power is 35152125121; divide this into groups of 3 digits (because 433 has 3 digits) and add: 35+152+125+121 = 433. A table of larger ones is located here. See also 7776.

(the meta-Fibonacci triangle)

464 is the sum of row 7 of the following triangle, which is similar to the fibonomial triangle which in turn resembles Pascal's triangle. I refer to the numbers in this triangle as meta-fibonomials:

1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 1 4 1 2 2 2 1 8 1 5 10 10 5 1 32 1 21 105 210 105 21 1 464 1 233 4893 24465 24465 4893 233 1 59184These numbers are defined similarly to the fibonomials, but involve terms of the form FFn, where Fn represents the nth Fibonacci number. For example, the 4th element in the 7th row (210) is FF6FF5FF4/FF3FF2FF1 = F8F5F3/F2F1F1 = 21×5×3/1×1×1. The general form is FFn...FFn-k+1/FFk...FF1. This formula always gives an integer, for reasons explained in the fibonomial description.

The second number on each row is the sequence of FFn (Sloane's A7570): 1,1,1,2,5,21,233,10946,5702887,.... The third number on each row is FFn×FFn-1, a sequence that starts: 1, 2, 10, 105, 4893, 2550418, 62423801102, ... The 4th number in each row is FFn×FFn+1×FFn+2/2, a sequence that starts 1, 2, 10, 210, 24465, 53558778, ....

If you start with a 3-digit number (with only a few exceptions) and repeat the "Kaprekar transformation", you'll always end up with 0 or with 495. In the Kaprekar transformation113, you reorder the digits largest-to-smallest, then subtract its reversal. For example, starting with 143, the reordering is 431 and the reversal of this is 134; subtracting gives 431-134 = 297. Continuing in a similar manner:

431 - 134 = 297

972 - 279 = 693

963 - 369 = 594

954 - 459 = 495

954 - 459 = 495 (etc.)

This works for all 3-digit numbers except multiples of 111, provided that you treat an answer "99" as if it is a 3-digit number "099".

For 4-digit numbers the ending value is 6174. So far as I know, there are no unique ending values for numbers with fewer than 3 or with more than 4 digits. For example, numbers with 5 digits have no ending value (all starting values end in a cycle of 2 or more values); numbers with 6 digits have two possible ending values (549945 or 631764), though most end in cycles; etc.

495, 6174, 549945, 631764, ... are members of OEIS sequence A099009.

(From Matthew Goers)

(a perfect number)

The third perfect number, defined as a number that is equal to the sum of its proper divisors (divisors smaller than itself): 1+2+4+8+16+31+62+124+248=496. The search for perfect numbers was considered an important problem to the mathematicians of the classical Greek era. If the sum is less than the number, it is called deficient, and if the sum is greater, it is called abundant.

As you can see, in this case of 496, all of the divisors are either powers of 2 (the 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16) or 31=25-1 times one of those powers of 2. Euclid, working ca. 300 BC, found this pattern and showed that if P is a prime number and if 2P-1 is also prime, then X given by

X = 2P-1 (2P - 1)

= 2N (2N+1 - 1)

is a perfect number. More recently is was shown that all even perfect numbers fit this pattern.

However, not all numbers that fit the pattern are perfect; see 2047 and 8384512. It is still not known if there are any odd perfect numbers.

Prime numbers of the form 2P-1 are called Mersenne primes. See my largenum notes for a (fairly) complete list of known perfect numbers.

There are also numbers whose proper divisors add up to exactly twice the number (see 120) or three or more times (see 30240 and 154345556085770649600).

See also 6, 28, 8589869056, and the largest known perfect number.

This is one of Clifford Pickover's "centered hexamorphic numbers" (or hexagonal automorphic numbers), defined as any n such that the nth centered hexagonal number 3n(n-1)+1 is equal to n modulo 10d, where d is the number of digits in n, i.e. d=floor(log10(n)+1). In other words, the decimal digits of 3n(n-1)+1 end with the digits of n. For example when n is 501, 3n(n-1)+1=751501 which ends in "501". Pickover found three infinite "families" of such numbers, one of which is represented by 501 (1, 51, 501, 5001, ...) and all of which are of the form 5×10k+1 for k=0,1,2,.... The other two such "families" are 6×(10k-1)/9+1 = 7, 67, 667, 6667, ... and 10k+1+6×(10k-1)/9+1 = 17, 167, 1667, 16667, .... See also 376. But there are others that don't fit any of those patterns, the first being 251. The centered hexamorphic numbers are: 0, 1, 7, 17, 51, 67, 167, 251, 417, 501, 667, 751, 917, 1251, 1667, 5001, 5417, 6251, 6667, 10417, 16667, 50001, 56251, 60417, 66667, 166667, 260417, ... (Sloane's sequence A94534).

This is 29 and is also the sum of 73 and 132. See also 728 and 4782969.

(a Carmichael number)

The first Carmichael number. Carmichael numbers are odd composite numbers which cannot be found to be composite using Fermat's Little Theorem, which states that for all prime numbers p, if n is relatively prime to p, then np-1-1 is divisible by p (sometimes stated: np - n is divisible by p, which is an equivalent statement). For a Carmichael number, no matter what n you pick this test will show that it might be prime. See also 1729.

The largest known Wilson prime, a prime number p for which (p-1)! + 1 is a multiple of p2. As shown by Wilson's theorem, all primes have the property that (p-1)! + 1 is divisible evenly by p, but Wilson primes have the additional property that you can divide by p a second time. Other Wilson primes include 5 and 13. The video by Numberphile (5 13 and 563) points out that despite the belief (based on statistical likelihood) that there "ought to be" an infinite number of them, no other Wilson prime is known; all primes less than 2×1013 have been checked.

This number is the goroawase equivalent (by a mixture of kunyomi and onyomi readings) of Konami, the name of a videogame company: 5 = こ (ko), 7 = な (na), 3 = み (mi). The number appears in cheat codes for some Konami games on mobile phone platforms, and in Dance Dance Revolution (see Konami Code).

See also 9001, 73735963, and 1597463007.

576 = 420×321×222. It is also a member of Somos' sequence A52129 associated with the constant 1.66168.... See also 1658880.

Leyland Primes

593 is a Leyland number because it can be expressed in the form xy + yx (specifically, with x=9 and y=2 or vice-versa). It is also prime, which makes it a "Leyland prime", so-called because primes of this form have been extensively studied by British mathematician Paul Leyland. Numberphile has a video about Leyland numbers here.

See also 32993, 5.19344×1015070 and 7.00558×1025049.

(Torah by one gematria system)

Common letter-number value of the word Torah in Hebrew. There are several Hebrew alphabetic number assignments used for Gematria (numerology) but only one system for the common purpose of communicating a number in ordinary text. It dates back to before they used separate symbols for the digits the way they do now. The assignment is as follows15:

א=1 ב=2 ג=3 ד=4 ה=5 ו=6 ז=7 ח=8 ט=9 י=10 כ=20 ל=30 מ=40 נ=50 ס=60 ע=70 פ=80 צ=90 ק=100 ר=200 ש=300 ת=400

Using that assignment, the value of תורה (Torah) is 611 (400+6+200+5). See also 187, 216, 611, 10000, and 304805.

Appears instead of 666 in Papyrus 115, the earliest known Greek manuscript of the relevant passage of the Bible (Revelation 13:18). For more, see the 666 page and in particular its gematria section.

The fouriest number of three digits or fewer (and thus a lesser-known "solution" to the four fours problem).

This number is automorphic because its square ends in itself: 6252=390625. Curiously, it is also a "triangular automorphic number" because the 625th triangular number, which is 625×(625+1)/2=195625, also ends in 625. The triangular automorphic numbers are Sloane's sequence A67270: 0, 1, 5, 25, 625, 9376, 90625, 890625, 7109376, 12890625, 212890625, 1787109376, ... According to the OEIS, David W. Wilson proved that every triangular automorphic number is also a normal (square) automorphic number. No proof is linked or described, but I have recreated it in my page on A67270. See also 501.

The first factor of a non-prime Fermat number. Fermat conjectured that the Fermat numbers were all prime, and could not factor 232+1=4294967297. In fact 4294967297 is composite, equal to 641 × 6700417. Euler showed that all factors of a Fermat number 22n+1 must be of the form K2n+1+1. In this case, n is 5 and the factor 641 is equal to 10×25+1+1. For more about this see the Wiki page on Fermat primes.

648 is the smallest number that can be expressed as a ba in two different ways: 3×63 = 2×182. Such numbers are not particularly common: 648, 2048, 4608, 5184, 41472, 52488, 472392, 500000, 524288, 2654208, 3125000, 4718592, ...

648 = 3×63 = 2×182

2048 = 8×28 = 2×322

4608 = 9×29 = 2×482

5184 = 4×64 = 3×123

41472 = 3×243 = 2×1442

52488 = 8×38 = 2×1622

472392 = 3×543 = 2×4862

500000 = 5×105 = 2×5002

524288 = 8×48 = 2×5122

2654208 = 3×963 = 2×11522

3125000 = 8×58 = 2×12502

4718592 = 18×218 = 2×15362

10125000 = 3×1503 = 2×22502

13436928 = 8×68 = 2×25922

21233664 = 4×484 = 3×1923

30233088 = 3×2163 = 2×38882

46118408 = 8×78 = 2×48022

76236552 = 3×2943 = 2×61742

134217728 = 8×88 = 2×81922

169869312 = 3×3843 = 2×92162

344373768 = 8×98 = 3×4863 = 2×131222

402653184 = 24×224 = 3×5123

512000000 = 5×405 = 2×160002

648000000 = 3×6003 = 2×180002

737894528 = 7×147 = 2×192082

800000000 = 8×108 = 2×200002

838860800 = 25×225 = 2×204802

922640625 = 5×455 = 3×6753

1147971528 = 3×7263 = 2×239582

1207959552 = 9×89 = 2×245762

1714871048 = 8×118 = 2×292822

1934917632 = 3×8643 = 2×311042

2754990144 = 4×1624 = 3×9723

3127772232 = 3×10143 = 2×395462

3439853568 = 8×128 = 2×414722

4879139328 = 3×11763 = 2×493922

6525845768 = 8×138 = 2×571222

6973568802 = 18×318 = 2×590492

7381125000 = 3×13503 = 2×607502

See also 344373768.

The square root of e to the power of 13. See 666 and 91. (From Raphie Frank98)

Main article: The number 666

Here are a few of the purely mathematical properties of 666:

666 is the sum of the squares of the first 7 primes: 22 + 32 + 52 + 72 + 112 + 132 + 172.

666 = 13 + 23 + 33 + 43 + 53 + 63 + 53 + 43 + 33 + 23 + 13. Such sums could be called "hyper-octahedral" numbers, based on a 4-dimensional polyhedron analogous to the octahedron.

It is the 36th triangular number: 1+2+3+...+36 = 666, which seems more significant because 36=6×6. 666 is the largest triangular number that is a repdigit. Because Roulette wheels have the numbers 1 through 36 (plus 0 and possibly also 00), 666 is the sum of the numbers on the Roulette wheel (and on a Roulette table, but not counting combination bets like "2nd 12" or "2-to-1").

See also 1000000000000066600000000000001 and 10(6.65565×10668)

This is 262, the first square that is a palindrome but whose square root is not a palindrome.

In the English language there are 26 letters, so 676 is the number of combinations of 2 letters when order is distinct. If the standard license plates in your area had 2 letters followed by 4 numbers, there would be 262×104 = 676×10000 = 6760000 possible plates.

"persistence" of numbers in Base 10

In 1973 N.J.A. Sloane described the process of multiplying the digits of a number together, and continuing until you get a non-changing result:

6×7×9 = 378; 3×7×8 = 168; 1×6×8 = 48; 4×8 = 32; 3×2 = 6; 6 = 6; 6 = 6; etc.

Starting with 679, we can perform the digit-multiplication five times until we get to a single-digit answer 6, and then the number no longer changes.

It's pretty easy to see that with every step the number gets smaller until you're down to a single digit (since 9×9 is less than 100, any three digits starting with 6 will give a product less than 600; a similar argument shows that any N digits starting with A will give a product less than A×10N-1), and so any such sequence will always end with a single-digit unchanging value.

Since it takes 5 steps starting with 679 to get to a single digit 6, Sloane says that the "persistence of 679 is 5. 679 is the smallest positive integer with a persistence of 5. The smallest number with a persistence of N for N=1, 2, 3, ... is OEIS sequence A003001: 10, 25, 39, 77, 679, 6788, 68889, ...

See also 39 and 277777788888899.

According to my classical sequence generator, 695 is the next number after my childhood "favourite" numbers 7, 27 and 127. The formula it finds is: A0 = 0; A1 = -1; AN+1 = N AN - AN + 2AN-1 + N (sequence MCS27694341). This serves as an example of how easy it is to find a sequence formula to match an arbitrary set of numbers. See also 715 and 1011.

The first 7 prime numbers (2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17) can be arranged to form the factors of 714 (2×3×7×17) and 715 (5×11×13). Because of this, the primorial 2×3×5×7×11×13×17=510510 is also an oblong number : 714×715=510510. The repeated digits come from 1001 being a factor.

714=21×34, so it is a golden rectangle number.

In base 714 there are easy tests for divisibility by 9 different primes (the 7 listed above plus 23 and 31 because 23×31=713). See the 14, 21, 29 and 66 entries for more about these properties.

714 and 715 also have the property that their prime factors add up to the same total: 2 + 3 + 7 + 17 = 5 + 11 + 13. Another (smaller) example is 77 and 78: 77=7×11, 78=2×3×13, and 7+11=2+3+13. When one of the pair is divisible by a square, it matters how you count the factors. For example, 24 and 25 are a pair if you count each prime only once: 24=2×2×2×3, 25=5×5, and 2+3=5. 15 and 16 qualify if you count the multiples: 15=3×5, 16=2×2×2×2, and 3+5=2+2+2+2. But the pair 714 and 715 qualify regardless of which way you define it.

Such pairs are called Ruth-Aaron pairs because of Babe Ruth's famous record of 714 career home runs, which was broken in 1974 when Hank Aaron hit his 715th. (Aaron reached 755 before retiring, but the number 715 is almost as commonly associated with him; in 2007 his record was surpassed by Bonds). Numberphile has a video on the topic, Aaron Numbers featuring Carl Pomerance who originally associated the names "Ruth-Aaron" to these pairs of numbers.

In Sloane's database of integer sequences, the relevant entries are A6145, A39752, and A39753. See also 7129199.

Part of a Ruth-Aaron pair, see 714.

Follows 3, 7, 27 and 127 in sequence MCS55651588, which is an alternative solution to the "problem" described in the entry for 695 found via my classical sequence generator. Another alternative solution is A136580, which would give 747. (As with 695, these numbers are interesting just by being an example of the ease of finding formulas that match a mystery integer sequence. The choice of this example is just as arbitrary as for 695; see its description. For me, 3 was not a favourite number in childhood, except through its connection to 27.)

Like 120 and 210, 720 can be expressed as a product of consecutive integers in two distinct ways: 2×3×4×5×6 = 8×9×10. You can also add a 7 to both sides and get a similar equation whose value is 5040. Here are the smallest numbers with this property: 120, 210, 720, 5040, 175560, 17297280, 19958400, 259459200, 20274183401472000, 25852016738884976640000, 368406749739154248105984000000, ... This is OEIS sequence A64224. The sequence is infinite — see 19958400 for details as to why. I also have a page dedicated to these numbers.

This is one less than 729 which is 93, and thus it is similar to 1729:

63 + 83 = 93 + -13.

This example mysteriously appears in Ramanujan's lost notebook, on page 82 (see this article) despite that it does not fit the pattern of the formulas and the other examples on that page. See also 336365328016955757248.

As it is also 123 - 103, 728 is expressible as a sum or difference of two cubes in three ways:

728 = 63 + 83 = 93 - 13 = 123 - 103

As the smallest positive integer with this property, 728 is the 3rd Cabtaxi number.

This is 3 to the power of 3!, a member of the fast-growing sequence NN! (OEIS sequence A53986; see also 281474976710656).

It is one of the cubes summing to Hardy's taxi number 1729, and the square of 27.

This number has the property that if you take any digit and move it down to the denominator, the result is still an integer: 42/7, 72/4, and 74/2 are all integers. Such numbers were investigated by Anant Pratap Singh and make up OEIS sequence A353729. All repdigits of course qualify, and the non-repdigit ones begin: 122, 124, 126, 142, 155, 162, 168, 186, 244, 248, 284, 324, 342, 366, 488, 648, 684, 728, 742, 1113, 1122, 1124, 1128, 1131, 1142, 1146, 1155, ... As one might expect, 1's and low digits are disproportionately represented. See also 8888111128.

744 is related to the integers approximated by expressions of the form eπ√n for certain special n, including most famously 163. See 640320 and Ramanujan constant.

One of the better-known numbers that is also a product or brand name: a well-known Boeing aircraft. 747 is also the sum of the first few even factorials: 0!+2!+4!+6! = 1+2+24+720 = 747. Sums of alternating factorials are Sloane's A136580; see also 715.

757 is the smallest factor of 999999999999999999999999999=1027-1 that is not also a factor of a smaller string of 9's, and therefore 757 is the smallest number whose reciprocal has a 27-digit repeating decimal: 1/757=.00132100396301188903566710700132... This is part of a series: 1/3 has a 1-digit pattern, 1/27 has a 3-digit pattern, and 1/757 has a 27-digit pattern. The series keeps going up (because if 1/n has a d-digit pattern, n is always larger than d), but computing the next number in the series is hard because it is equivalent to factoring a large number like 10757-1. See also 7, 27 and 239.

The number of distinct, legal positions in Tic-tac-toe, ignoring rotations and reflections.

See also 26830.

Like 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, 192 and 384, 768 is a 3-smooth number of the form 3×2n. It is one of several such numbers to occur in personal computer display dimensions (in this case, the standard 1024×768 "XGA" mode); see also 192.

See 82944.

As Matt Parker points out in his book in maths errors Humble Pi, there have been many chain email hoaxes concerning a calendar-related event that is claimed (incorrectly) to be very rare. Curiously, these hoaxes all cite the oddly-specific number 823 as the number of years until the special event would happen again. One example:

December calendar. (This will be the only time you will see this phenomenon in your life.) [Picture of a grid of numbers representing a month with 31 days starting on a Saturday] The month of December this year will have 5 Saturdays 5 Sundays and 5 Mondays. It only happens once every 823 years. The Chinese call it "BAG FULL OF MONEY". Send this message to all your friends [...]

This began circulating in 2018, and was so popular it was still being forwarded a year later. The occasion of a December with 5 Saturdays, Sundays and Mondays actually happens four times out of every 28 years; including 2001, 2007, 2012, 2018, 2029, 2035, and so on (the intervals are 6, 5, 6, 11 and then it repeats; the pattern is broken at the end of the century because 2100 is not a leap year). Even more absurd is this one, recently appearing in the lead-up to February 2022:

This coming February cannot come in your life time again. Because this year February has

4 Sundays, 4 Mondays, 4 Tuesdays, 4 Wednesdays, 4 Thursdays, 4 Fridays & 4 Saturdays.

This Happens once every 823 years. This is called money bags. So send to at least 5 people or 5 Groups and hopefully money will arrive within 4 days. Based on Chinese Feng Shui. Send within 11 minutes of reading.

Needless to say, the occurance of a February with 4 of each day is just the same as saying that February has 28 days, which happens often enough that it is guaranteed at least once every 823 days, not years. This particular family of hoaxes goes back to 2010 or earlier and is addressed by the Snopes article Money Bags Calendar.

840 is a record-setter for having more divisors than any smaller number, and it is the first such record-setter that does not also appear as the number of divisors of another record-setter99. See also 12, 45360, 720720, 3603600, 245044800, 293318625600, 195643523275200, 278914005382139703576000, 2054221614063184107682218077003539824552559296000 and 457936×10917.

841 = 292 is the sum of two consecutive squares: 202+212. This is the second smallest example; the smallest is 52 = 25 = 32+42. The series continues: 52, 292, 1692, 9852, 57412, 334612, 1950252, ... (Sloane's integer sequence A1653; my MCS13882118). This sequence consists of every other Pell number; Each of these is 6 times the previous one minus the one before that, for example, 169 = 6×29-5. See also 99 and 204.

854 is 53+93, and 855 is 73+83. Like 10744, the two sums fit the form (2t2-t-1)3+(2t2+t-1)3 and (2t2-1)3+(2t2)3; in this case t=2. (from Vladimir Shevelev) See also 18426689288.

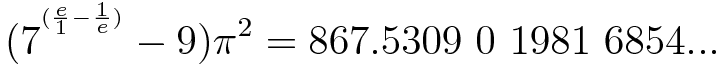

According to xkcd's Randall Munroe[226], "Jenny's Constant" is:

Munroe, for whom π is a favourite element of humorous formulas (for example see xkcd 687), might have found this formula using RIES. Putting 867.5309 into RIES directly does not give this formula or anything like it, but 867.5309 divided by π2 is 87.8992576343025..., and when this number is given to RIES, it finds:

log_7(x+9) = e-1/e for x = T + 2.00787e-07 {109}The phone number in the song is more commonly thought of as being the integer 8675309 (a twin prime, as Munroe handily notes in the mouseover text for the comic), but Munroe's formula is arguably better. Following the digits of the phone number itself, "Jenny's Constant" gives the year in which the song was recorded: 1981 (a fact noticed by Rob Johnson of the explainxkcd forums).

In an early published example[133] of the four fours problem, it was stated that one could get as high as 112 using the standard rules (square roots allowed, concatenation e.g. two 4's make 44; decimal points e.g. two 4's make 4/.4 = 10); and if you allow subfactorials you can get as high as 877.

The smallest odd "abundant" number: the sum of its factors is larger than the number itself. The odd abundant numbers, Sloane's A5231, are: 945, 1575, 2205, 2835, 3465, 4095, ... There are far more even abundant numbers (Sloane's A5101).

952 is the sum of the cubes of its digits plus the product of its digits: 952 = 93+53+23+9×5×2. (Thanks to Cyril Soler for this tip)

The number of cells in the nematode worm C. elegans, heavily studied and used as a test animal in science. Barring rare mutation or harsh environmental conditions, every worm is exactly the same. It has 95 muscles and 302 neurons. The neurons signal the muscles at 1410 points and connect with each other at 6393 synapses. Its genome has been completely sequenced, with approximately 20405 protein-coding genes and precisely 100267633 DNA base pairs.

1/998 = 0.001002004008016032064128256513026052104208416833667334669..., a repeating decimal in which the powers of 2 appear one after another (until they start to overlap and break the pattern)

0.001 0.000002 0.000000004 0.000000000008 0.000000000000016 0.000000000000000032 0.000000000000000000064 0.000000000000000000000128 0.000000000000000000000000256 0.000000000000000000000000000512 0.000000000000000000000000000001024 0.000000000000000000000000000000002048 + ... ... --------------------------------------------- 0.001002004008016032064128256513026052...The same thing happens to a lesser degree in the digits of 1/98, and to a greater degree in the digits of 1/9998, 1/99998, etc. The reason for the pattern is easy to see if you consider how long division is performed, or just notice that 1/998 = (0.998+0.002)/998 = 0.001 + 2 × (0.001 × 1/998). The same phenomenon is responsible for the powers of 3 in the digits of 1/997, and so on. A similar pattern involving the Fibonacci numbers appears in the reciprocals of 89 and 9899. For more of this type of decimal fraction, see my separate article Fractions with Special Digit Sequences; see also 99.9998, 199, 9801, and 997002999.

Because 1002004... is similar to 1002001 which is the square of

1001, the square roots of numbers like 2/49.9 (where 2 and 499 are the factors of 998) have really cool digit patterns:

√2/49.9 = 0.2 002 003 005 008...

These digits are related to the series expansion of √1/(1-2x), as is explained in the entry for the square root of 62. See also 99.9998, 999998.

The casting out nines principle works for 99, 999, 9999 and so on. For the same reason that "casting" gives us an easy way to test for divisibility by 3, it also allows us to test easily for divisibility by 11, since 11 is a factor of 99, and for divisibility by the factors of 999, which are 27 and 37.

Because 27×37=999, the reciprocals of 27 and 37 contain each other as digits:

1/27 = 0.037037037037037...

1/37 = 0.027027027027027...

The same relationship exists between any two numbers whose product is 10N-1 for some N. After the initial few, which are just minor variations on 1/3 = 0.33333... and 1/9 = 0.11111..., a lot of more interesting examples are found:

3 and 3: 1/3 = 0.333333...

1 and 9: 1/9 = 0.111111... and 1/1 = 0.999999...

9 and 11: 1/11 = 0.0909090909... and 1/9 = 0.1111111111...

99 and 101: 1/101 = 0.0099009900990099...

and 1/99 = 0.0101010101010101...

33 and 303: 1/303 = 0.0033003300330033...

and 1/33 = 0.0303030303030303...

271 and 369: 1/369 = 0.0027100271002710027100271...

and 1/271 = 0.0036900369003690036900369...

123 and 813: 1/813 = 0.0012300123001230012300123...

and 1/123 = 0.0081300813008130081300813...

693 and 1443: 1/1443 = 0.000693000693000693000693000693000693...

and 1/693 = 0.001443001443001443001443001443001443...

819 and 1221: 1/1221 = 0.000819000819000819000819000819000819...

and 1/819 = 0.001221001221001221001221001221001221...

2151 and 4649: 1/4649 = 0.000215100021510002151000215100021510002151...

and 1/2151 = 0.000464900046490004649000464900046490004649...

7227 and 13837: 1/13837 = 0.0000722700007227000072270000722700007227...

and 1/7227 = 0.0001383700013837000138370001383700013837...

7373 and 13563: 1/13563 = 0.0000737300007373000073730000737300007373...

and 1/7373 = 0.0001356300013563000135630001356300013563...

and so on. See also 99.9998 and 101.

999 is an example of a "repdigit", a number consisting of the same digit repeated a number of times. Repdigits often come up in the study of numbers that have properties relating to the sum of their digits, repeating decimal fractions, etc. For example, many Kaprekar numbers are repdigits, or are closely related to them; repdigits and factors thereof also appear in the sequences A7138 and A61075 related to repeating decimal fractions whose repeating part has N digits.

(a thousand)

Thousand is another number that, for most of us, temporarily holds the honor of being the biggest number we've heard of. Usually it replaces 100 in this role and is overtaken by 1000000.

When numbers get big, we tend to group the digits in 3's to make the numbers easier to read: 134,217,728 instead of 134217728. That causes people to pay a little more attention to groups of 3 digits than they otherwise would. For example, it's probably the main reason why I discovered this formula for 227. Sometimes it's almost as if we're working in base 1000.

The neighboring numbers 999 and 1001 also frequently play a role — if the phenomenon being investigated involves adding groups of 3 digits together, then it is related to divisibility by 999. If it involves a similarity between adjacent groups of 3 digits (such as 720720) it is related to divisibility by 1001. The two sometimes get inter-related when division is involved because 1/999 is 0.001001001001... and 1/1001 is 0.000999000999...; see also 999999.

1001 is a product of three consecutive primes: 1001 = 7×11×13. This sequence runs: 30, 105, 385, 1001, 2431, 4199, 7429, 12673, 20677, 33263, 47027, ... (OEIS sequence A46301). See also 77.

1001 is also (11×12×13×14)/24, the product of four consecutive numbers divided by 24. The expression x(x+1)(x+2)(x+3) is always evenly divisible by 24, and all such numbers (for positive integer x) are in the 5th diagonal of Pascal's triangle.

Peter J. Cameron, author of this book on combinatorics, "[was] in Vancouver in 1984 [and] saw a Dutch pancake house advertising 'a thousand and one combinations' of toppings". Naturally he deduced that the number of toppings offered was 14, from which precisely four must be chosen by the customer: 14!/(10!×4!) = 1001. He was told that in fact there were 25 toppings available, and any number could be chosen (thus allowing 225=33554432 combinations). See also 40312, 4.3252...×1019, and 10137.

Simplex (or "Hyper-Tetrahedral") Numbers

Because of its being in the 5th diagonal of Pascal's triangle, 1001 is a sum of successive tetrahedral numbers, in this case the first 11: 1+4+10+20+35+56+84+120+165+220+286=1001. This makes it a "hypertetrahedral number". The four-dimensional analogue of a tetrahedron is called a "4-simplex" or a "5-cell" so we might also refer to these as "simplex numbers", though that necessitates another name for the 5th dimension and so on; for that reason the more obscure names pentachoron and pentatope might be better.

Like the triangular and tetrahedral numbers, a sequence of integers can be associated with the 4-simplex shape according to how many objects of a round or "spherical" shape can be neatly arranged into that shape (though at higher dimensions there are far denser packings, see e.g. 240). Also like the triangular and tetrahedral numbers, the simplex numbers appear as one of the "diagonals" of Pascal's triangle. The sequence of simplex numbers runs: 1, 5, 15, 35, 70, 126, 210, 330, 495, 715, 1001, 1365, 1820, ... (Sloane's A0332). As the OEIS entry tells us, these happen to be "Figurate numbers based on the 4-dimensional regular convex polytope called the regular 4-simplex, pentachoron, 5-cell, pentatope or 4-hypertetrahedron with Schlaefli symbol {3,3,3}".

1001 is related in various ways to many numbers and number phenomena that have repeated sets of 3 digits, and some of these, like 720720, occur because 1001 is a product of three consecutive primes.

In One Thousand and One Nights, also known as 1001 Arabian Nights, concerns a very long period of time during which a series of stories and stories-within-stories are told by the narrator to avoid being killed by a king. There are many versions, including some that are actually organised into 1001 parts, all of suitable length for reading at bedtime and most of them ending in cliffhangers. 1001 nights is 143 weeks, nearly 3 years.

There is evidence of early versions of the Arabian Nights story collection, apparently an anthology of material originating in oral tradition, with far fewer than 1001 parts. 1001 was acquired and stuck because it represents "a lot" in a special way. The reader is probably familiar with similar uses of "101", "201", "501", and similar numbers in other contexts.

See also 999, 1000, 2001, 999999, 3603600, and this description of highly composite numbers.

First page . . . Back to page 11 . . . Forward to page 13 . . . Last page (page 25)

Quick index: if you're looking for a specific number, start with whichever of these is closest: 0.065988... 1 1.618033... 3.141592... 4 12 16 21 24 29 39 46 52 64 68 89 107 137.03599... 158 231 256 365 616 714 1024 1729 4181 10080 45360 262144 1969920 73939133 4294967297 5×1011 1018 5.4×1027 1040 5.21...×1078 1.29...×10865 1040000 109152051 101036 101010100 — — footnotes Also, check out my large numbers and integer sequences pages.

s.30

s.30